While conducting an investigation into an attack in July in which the attackers repeatedly attempted to infect computers with Maze ransomware, analysts with Sophos’ Managed Threat Response (MTR) discovered that the attackers had adopted a technique pioneered by the threat actors behind Ragnar Locker earlier this year, in which the ransomware payload was distributed inside of a virtual machine (VM).

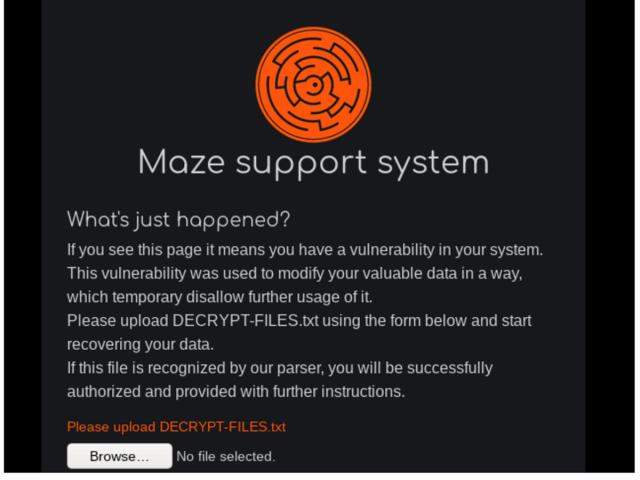

Another ransomware trend is “secondary extortion,” where alongside the data encryption the attackers steal and threaten to publish sensitive or confidential information, if their demands are not met. In 2020, Sophos reported on Maze, RagnarLocker, Netwalker, REvil, and others using this approach. Most of the time, Sophos Home detects and blocks the ransomware immediately. In the event that the attack becomes successful, it is important to ensure that the Sophos Home installed is properly working. Check that it is updating and reporting the status to your dashboard correctly. The Sophos Managed Threat Response (MTR) team was called in to help an organization targeted with Maze ransomware. The attackers issued a ransom demand for US$15 million – if they had succeeded this would have been one of the most expense ransomware payments to date. Background: Ransomware partners in crime. Sophos Intercept X protects against all type of ransomware attacks as it works on behaviour, not based on Signature-based detection. So, It provides better protection against the 'Zero-day attacks' as mentioned by u/-Reddit-Mark. Sophos Intercept X advanced license provides Signature + Behaviour-based detection which makes it better product and If you have EDR and then it. How Ransomware Attacks What defenders should know about the most prevalent and persistent malware families Ransomware’s behavior is its Achilles' heel, which is why Sophos spends so much time studying it. In this report, we've assembled some of the behavioral patterns of the ten most common, damaging, and persistent ransomware families.

In the Maze incident, the threat actors distributed the file-encrypting payload of the ransomware on the VM’s virtual hard drive (a VirtualBox virtual disk image (.vdi) file), which was delivered inside of a Windows .msi installer file more than 700MB in size. The attackers also bundled a stripped down, 11 year old copy of the VirtualBox hypervisor inside the .msi file, which runs the VM as a “headless” device, with no user-facing interface.

The Maze-delivered virtual machine was running Windows 7, as opposed to the Windows XP VM distributed in the Ragnar Locker incident. A threat hunt through telemetry data initially indicated the attackers may have been present on the attack target’s network for at least three days prior to the attack beginning in earnest, but subsequent analysis revealed that the attackers had penetrated the network at least six days prior to delivering the ransomware payload.

The investigation also turned up several installer scripts that revealed the attackers’ tactics, and found that the attackers had spent days preparing to launch the ransomware by building lists of IP addresses inside the target’s network, using one of the target’s domain controller servers, and exfiltrating data to cloud storage provider Mega.nz.

The threat actors initially demanded a $15 million ransom from the target of the attack. The target did not pay the ransom.

How the attack transpired

Subsequent analysis by the MTR team revealed that the attackers orchestrated the attack using batch files, and made multiple attempts to maliciously encrypt machines on the network; The first iteration of ransomware payloads were all copied to the root of the %programdata% folder, using the filenames enc.exe, enc6.exe, and network.dll. The attackers then created scheduled tasks that would launch the ransomware with names based on variants of Windows Update Security or Windows Update Security Patches.

The initial attack did not produce the desired result; The attackers made a second attempt, with a ransomware payload named license.exe, launched from the same location. But before they launched it, they executed a script that disabled Windows Defender’s Real-Time Monitoring feature.

The attackers then, once again, executed a command that would create a scheduled task on each computer they had copied the license.exe payload to, this time named Google Chrome Security Update, and set it up to run once at midnight (in the local time zone of the infected computers).

These detections indicate that the ransomware payloads were being caught and quarantined on machines protected by Sophos endpoint products before they could cause harm. Sophos analysts started to see detections that indicated the malware was triggering the Cryptoguard behavioral protections of Intercept X. In this case, Cryptoguard was preventing the malware from encrypting files by intercepting and neutralizing the Windows APIs that the ransomware was attempting to use to encrypt the hard drive.

So the attackers decided to try a more radical approach for their third attempt.

Weaponized virtual machine

The Maze attackers delivered the attack components for the third attack in the form of an .msi installer file. Inside of the .msi was an installer for both the 32-bit and 64-bit versions of VirtualBox 3.0.4. This version dates back to 2009 and is still branded with its then-publisher’s name, Sun Microsystems.

The .msi also contains a 1.9GB (uncompressed) virtual disk named micro.vdi, which itself contains a bootable partition of Windows 7 SP1, and a file named micro.xml that contains configuration information for the virtual hard drive and session.

The root of that virtual disk contained three files associated with the Maze ransomware: preload.bat, vrun.exe, and a file just named payload (with no file extension), which is the actual Maze DLL payload.

The DLL file has a different, internal name for itself.

The preload.bat file (shown below) modifies the computer name of the virtual machine, generating a series of random numbers to use as the name, and joins the virtual machine to the network domain of the victim organization’s network using a WMI command-line function.

The virtual machine was, apparently, configured in advance by someone who knew something about the victim’s network, because its configuration file (“micro.xml”) maps two drive letters that are used as shared network drives in this particular organization, presumably so it can encrypt the files on those shares as well as on the local machine. It also creates a folder in C:SDRSMLINK and shares this folder with the rest of the network.

At some point (it’s unclear when and how, exactly, it accomplished this), the malware also writes out a file named startup_vrun.bat. We found this file in c:usersAdministratorAppDataRoamingMicrosoftWindowsStart MenuStartup, which means it’s a persistence mechanism that relies on the computer rebooting before the attackers launch the malware.

The script copies the same three files found on the root of the VM disk (the vrun.exe and payload DLL binaries, and the preload.bat batch script) to other disks, then issues a command to shut down the computer immediately. When someone powers the computer on again, the script executes vrun.exe.

The C:SDRSMLINK folder location, created when the .msi file first runs, acts as a clearinghouse for specific folders the malware wants to track. It’s full of symbolic links (symlinks, similar to Windows shortcuts) to folders on the local hard drive.

The Ragnar Locker connection

The technique used in the third attack is completely different to those used before by the threat actors behind Maze, but the investigators recognized it immediately because the team who responded to this Maze attack are the same team that responded to the Ragnar Locker ransomware attack, where the technique was first seen.

In Sophos’ earlier reporting about Ragnar Locker, we wrote that “Ragnar Locker ransomware was deployed inside an Oracle VirtualBox Windows XP virtual machine. The attack payload was a 122 MB installer with a 282 MB virtual image inside—all to conceal a 49 kB ransomware executable.” MITRE has subsequently added this technique to its ATT&CK framework.

The Maze attackers took a slightly different approach, using a virtual Windows 7 machine instead of XP. This significantly increased the size of the virtual disk, but also adds some new functionality that wasn’t available in the Ragnar Locker version. The threat actors bundled a VirtualBox installer and the weaponized VM virtual drive inside a file named pikujuwusewa.msi. The attackers then used a batch script called starter.bat.to launch the attack from within the VM.

The virtual machine (VM) that Sophos extracted from the Maze attack shows that this (newer) VM is configured in such a way that it allows easy insertion of another ransomware on the attacker’s ‘builder’ machine. But the cost in terms of size is signficant: The Ragnar Locker virtual disk was only a quarter the size of the nearly 2GB virtual disk used in the Maze attack—all just to conceal one 494 KB ransomware executable from detection.

| Ragnar Locker | Maze | |

| MSI installer | 122 MB OracleVA.msi | 733 MB pikujuwusewa.msi |

| Virtual Disk Image (VDI) | 282 MB micro.vdi | 1.90 GB micro.vdi |

| Ransomware binary in VDI | 49 KB vrun.exe | 494 KB payload |

The attackers also executed the following commands on the host computer during the Maze attack:

This ran the Microsoft Installer that installs VirtualBox and the virtual hard drive.

They stop the Volume Shadow Copy service; the ransomware itself includes a command to delete existing shadow copies.

They halt SQL services to ensure that they can encrypt any databases.

Sophos Maze Ransomware Protection

They attempt to stop Sophos endpoint protection services (which fails).

Finally, they start the VirtualBox service and launch the VM.

The future of ransomware?

The Maze threat actors have proven to be adept at adopting the techniques demonstrated to be successful by other ransomware gangs, including the use of extortion as a means to extract payment from victims. As endpoint protection products improve their abilities to defend against ransomware, attackers are forced to expend greater effort to make an end-run around those protections.

Sophos endpoint products detect components of this attack as Troj/Ransom-GAV or Troj/Swrort-EG. Indicators of compromise can be found on the SophosLabs Github.

Ransomware operators are always on the lookout for a way to take their ransomware to the next level. That’s particularly true of the gang behind LockBit. Following the lead of the Maze and REvil ransomware crime rings, LockBit’s operators are now threatening to leak the data of their victims in order to extort payment. And the ransomware itself also includes a number of technical improvements that show LockBit’s developers are climbing the ransomware learning curve—and have developed an interesting technique to circumvent Windows’ User Account Control (UAC).

Because of recent dynamics in the ransomware world, we suspect that this privilege-escalation technique will pop up in other ransomware families in the future. We’ve seen a surge in “imposter” ransomware that are essentially rebranded variants of already-existing ransomware. Not a single day goes by where a new brand of ransomware does not come out. It has become surprisingly easy to clone ransomware and release it, with small modifications, under a different umbrella.

The Ransomware Learning Curve

Before we jump into the synopsis of LockBit, let’s take a moment to look at how ransomware is developed, in general. Many families follow a common timeline when it comes to the techniques and procedures ransomware developers implement at each stage. This appears to stem from the learning curve involved in creating ransomware, and the iteration of the malware as the developer builds his or her related knowledge of the malware craft.

Each ransomware seems to have an “infancy phase,” where the developer implements TTPs hastily just so the “product” can come out and start gaining its reputation. In this phase, the simplest ideas are implemented first, strings are usually plain text, the encryption is implemented in a way that only a single-thread is used, and LanguageID checks are in place to avoid encrypting computers in CIS countries. and avoid attracting unwanted attention from CIS law enforcement agencies.

After about 2 months into the ransomware operation, the developer starts implementing more sophisticated elements. They may introduce multi-threading, establish a presence in underground forums, obfuscate or encrypt strings in the binary, and there is usually a skip list/kill list for services and processes.

Around 4 months into the ransomware’s life, we start seeing things get more serious. The business model may now switch to Ransomware as a Service (RaaS), putting an Affiliate program in place. Oftentimes, binaries are cryptographically signed with valid, stolen certificates. There is a possibility that the ransomware developer starts implementing UAC bypasses at this stage. This appears to be the stage the LockBit group is entering.

Advertising the goods

As with most ransomware, LockBit maintains a forum topic on a well-known underground web board to promote their product. Ransomware operators maintain a forum presence mainly to advertise the ransomware, discuss customer inquiries and bugs, and to advertise an affiliate program through which other criminals can lease components of the ransomware code to build their own ransomware and infrastructure.

In January, LockBit’s operators created a new thread in the web board’s marketplace forum, announcing the “LockBit Cryptolocker Affiliate Program” and advertising the capabilities of their malware. The post claims that the new version had been in development since September of 2019, and emphasizes the performance of the encryptor and its lower use of system resources to prevent its detection.

LockBit’s post indicates that “we do not work in the CIS,” meaning that the ransomware will not target victims in Russia and other Commonwealth of Independent States countries. This comes as no surprise—as we have seen previously, CIS authorities don’t bother investigating these groups unless they are operating against targets in their area of jurisdiction.

Sophos Maze Ransomware Download

That does not mean that the LockBit group won’t do business with other CIS-based gangs. In fact, they won’t work with English-speaking developers without a Russian-speaking “guarantor” to vouch for them.

Escalating the extortion

In this most recent evolution of LockBit, the malware now drops a ransom note that threatens to leak data the malware has stolen from victims: “!!! We also download huge amount of your private data, including finance information, clients personal info, network diagrams, passwords and so on. Don’t forget about GDPR.”

If the threat were to be carried out, it might result in real-world sanctions against the ransomware victims from regulators or privacy authorities—for example, for violating the European Union’s General Data Privacy Rules (GDPR) that make companies responsible for securing sensitive customer data in their possession.

An increasing number of ransomware gangs use extortion that threatens the release of private data, which might include sensitive customer information, trade secrets, or embarrassing correspondence to incentivize victims to pay the ransom, even if they have backups that prevented data loss. The data leak threat has become a signature of the REvil and Maze ransomware gangs; the Maze group has gone as far as to publicly publish chunks of data from victims who fail to pay by the deadline, taking down the dumps when they are finally paid.

Picking through LockBit’s code

From a first glance at the recent LockBit sample with a reverse-engineering tool, we can tell that the program was written primarily in C++ with some additions made using Assembler. For example, a few anti-debug techniques employ the fs:30h function call to manually check the PEB (Process Environment Block) for the BeingDebugged flag, instead of using IsDebuggerPresent().

The first thing the ransomware does at execution is to check whether the sample was executed with any parameters added from the command line. Usually, this is done to check for whether the sample is being executed in a sandbox environment. Contemporary malware often requires that the command to run the malware use specific parameters to prevent the malware from being analyzed by an automated sandbox, which often execute samples without parameters. But the LockBit sample we examined doesn’t do that—it won’t execute if there is any parameter entered from the command line. If there are no arguments in the command that executes it, Lockbit hides its console output, where the malware prints debug messages, and proceeds to do its job.

This could be intended to detect if the sample was executed in a sandbox environment. But it’s possible that either the malware author made a mistake in the implementation of the check (and wanted to check the other way around), or that this behavior is just a placeholder, and future versions will introduce different logic.

Hiding strings

LockBit’s author also used several techniques to make it more difficult to reconstruct the code behind it. The Portable Executable (PE) binary shows signs of being heavily optimized, as well as some efforts by the group to cover their coding tracks—or at least get rid of some of the low-hanging fruit that reverse engineering tools look for, such as unencrypted text strings.

These string variables get decrypted on the fly with a 1-byte XOR key unique to each string: the first hex byte of every variable.

Almost all the functions contain a small routine that loops around and is in charge of decrypting hidden strings. In this case, we can see that how the original MSSQLServerADHelper100 service name gets de-obfuscated: the malware leverages a one-byte “0A” XOR key to decrypt the plaintext service name.

Check your privilege

To ensure that it can do the most damage possible, LockBit has a procedure to check whether its process has Administrator privileges. And if it doesn’t, it uses a technique that is growing in popularity among malware developers: a Windows User Account Control (UAC) bypass.

Leveraging OpenProcessToken, it queries the current process via a TOKEN_QUERY access mask. After that, it calls CreateWellKnownSid to create a user security identifier (SID) that matches the administrator group (WinBuiltinAdministratorsSid), so now the malware has a reference it can use for comparisons. Finally, it checks whether the current process privileges are sufficient for Administrator rights, with a call to CheckTokenMembership.

If the current process does not have Admin privileges, the ransomware tries to sidestep Windows UAC with a bypass. In order for that to succeed, a Windows COM object needs to auto-elevate to Admin-level access first.

To make this possible, LockBit calls a procedure called supMasqueradeProcess upon process initialization. Using supMasqueradeProcess allows LockBit to conceal its process’ information by injecting into a process running in a trusted directory. And what better target is there for that than explorer.exe?

The source code for the masquerade procedure can be found in a Github repository.

With the use of IDA Pro’s COM helper tool, we see two CLSIDs—globally unique identifiers that identify COM class object—that LockBit’s code references. CLSIDs, represented as 128-bit hexadecimal numbers within a pair of curly braces, are stored in the Registry path HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINESoftwareClassesCLSID.

Looking up these reveals that the two CSLIDS belong to IColorDataProxy and ICMLuaUtil—both undocumented COM interfaces that are prone to UAC bypass.

| Name | CLSID | DLL |

| CMSTPLUA | {3E5FC7F9-9A51-4367-9063-A120244FBEC7} | ..system32cmstplua.dll |

| Color Management | {D2E7041B-2927-42fb-8E9F-7CE93B6DC937} | ..system32colorui.dll |

Masquerading as explorer.exe, LockBit calls CoInitializeEx to initialize the COM library, with COINIT_MULTITHREADED and COINIT_DISABLE_OLE1DDE flags to set the concurrency model. The hex values here (CLSIDs) are then moved and aligned into the stack segment register, and the next function call (lockbit.413980) will further use them.

Lockbit.413980 hosts the COM elevation moniker, which allows applications that are running under user account control (UAC) to activate COM classes (via the following format: Elevation:Administrator!new:{guid} ) with elevated privileges.

The malware adds the 2 previously seen CLSIDs to the moniker and executes them.

Now, the privilege has been successfully elevated with the UAC bypass and the control flow is passed back to the ransomware. We also notice two events and a registry key change during the execution:

| C:WINDOWSSysWOW64DllHost.exe /Processid:{3E5FC7F9-9A51-4367-9063-A120244FBEC7} |

| C:WINDOWSSysWOW64DllHost.exe /Processid:{D2E7041B-2927-42fb-8E9F-7CE93B6DC937} |

| Key: SoftwareMicrosoftWindows NTCurrentVersionICMCalibration |

| Value: DisplayCalibrator |

Kill or skip

LockBit enumerates the currently running processes and started services via the API calls CreateToolhelp32Snapshot, Process32First, Process32Next and finally OpenProcess, and compares the names against an internal service and process list. If one process matches with one on the list, LockBit will attempt to terminate it via TerminateProcess.

The procedure to kill a service is a bit different. The malware will first connect to the Service Control Manager via OpenSCManagerA. It then attempts to check whether a service from the list exists via OpenServiceA. If the targeted service is present, it then tries to determine its state by calling to QueryServiceStatusEx. Based on the status returned, it will call ControlService with the parameter SERVICE_CONTROL_STOP (0x00000001) on the specific service to stop it. But before that, another function (0x40F310) will cycle through all dependent services in conjunction with the target service, so dependencies are stopped too. The malware will initiate calls to EnumDependentServicesA to achieve this.

The services that the malware tries to stop include anti-virus software (to avoid detection) and backup solution services. (Sophos is not affected by this attempt.) Other services are stopped because they might lock files on the disk, and might make it more difficult for the ransomware to easily acquire handles to files—stopping them improves LockBit’s effectiveness.

Some of the services of note that the ransomware attempts to stop, in the order they are coded into the ransomware, are:

| DefWatch | Symantec Defwatch |

| ccEvtMgr | Norton AntiVirus Event Manager Service |

| ccSetMgr | Symantec Common Client Settings Manager Service |

| SavRoam | Symantec AntiVirus suite |

| RTVscan | Symantec AntiVirus |

| QBFCService | QuickBooks is an accounting software |

| QBIDPService | QuickBooks for Windows by Intuit, Inc.. |

| Intuit.QuickBooks.FCS | QuickBooks for Windows by Intuit, Inc.. |

| QBCFMonitorService | QuickBooks for Windows by Intuit, Inc.. |

| YooBackup | Wooxo Backup |

| YooIT | Wooxo Backup |

| zhudongfangyu | 360 by Qihoo 360 Deep Scan |

| sophos | Sophos |

| stc_raw_agent | STC Raw Backup Agent |

| VSNAPVSS | StorageCraft Volume Snapshot VSS Provider |

| VeeamTransportSvc | Veeam Backup Transport Service |

| VeeamDeploymentService | Veeam Deployment Service |

| VeeamNFSSvc | Veeam Backup and Replication Service |

| veeam | Veeam |

| PDVFSService | Veritas Backup Exec PureDisk Filesystem |

| BackupExecVSSProvider | Veritas Backup Exec VSS Provider |

| BackupExecAgentAccelerator | Veritas Backup Exec Agent Accelerator |

| BackupExecAgentBrowser | Veritas Backup Exec Agent Browser |

| BackupExecDiveciMediaService | Veritas Backup Exec Media Service |

| BackupExecJobEngine | Veritas Backup Exec Job Engine |

| BackupExecManagementService | Veritas Backup Exec Management Service |

| BackupExecRPCService | Veritas Backup Exec RPC Service |

| AcrSch2Svc | Acronis Scheduler Service |

| AcronisAgent | Acronis Agent |

| CASAD2DWebSvc | Arcserve UDP Agent service |

| CAARCUpdateSvc | Arcserve UDP Update service |

In addition to the list of services to kill, LockBit also carries a list of things not to encrypt, including certain folders, specific files and files with certain extensions that are important to the operating system—since disabling the operating system would make it difficult for the victim to receive and act upon the ransom note. These are stored in obfuscated lists within the code (shown below), A function within LockBit uses the FindFirstFileExW and FindNextFileW API calls to read through the file names and folder names on the targeted disk, and then a simple lstrcmpiW function is called to compare the hardcoded list with those names.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Accelerating file encryption

Recently, we have seen ransomware groups taking more advanced concepts and applying it to their craft. One of these advanced concepts applied in LockBit is the use of Input/Output Completion Ports (IOCPs).

IOCPs are a model for creating a queue to efficient threads to process multiple asynchronous I/O requests. They allow processes to handle many concurrent asynchronous I/O more quickly and efficiently without having to create new threads each time they get an I/O request.

That capability makes them well-suited to ransomware. The sole purpose of ransomware is to encrypt as many delicate files as possible, rendering the user’s data useless. REvil (Sodinokibi) ransomware also uses IOCPs to achieve higher encryption performance.

LockBit’s aim was to be much faster than any other multi-threaded locker. The group behind the ransomware claims to have used the following methods to boost the performance of their file encryption:

- Open files with the FILE_FLAG_NO_BUFFERING flag, write by sector size

- Transfer work with files to Native API

- Use asynchronous file I/O

- Use I/O port completion

- Pass control to the kernel yourself, google KiFastSystemCall

Once a file is marked for encryption—meaning, it did not match entries on the skip-list—a LockBit routine checks whether the file already has a .lockbit extension. If it does not, it encrypts the file and appends the .lockbit extension to the end of the filename.

Lockbit relies on LoadLibraryA and GetProcAddress to load bcrypt.dll and import the BCryptGenRandom function. If the malware successfully imports that DLL, it uses BCRYPT_USE_SYSTEM_PREFERRED_RNG which means use the system-preferred random number generator algorithm. If the malware was unsuccessful calling bcrypt.dll, it invokes CryptAcquireContextW and CryptGenRandom to invoke the Microsoft Base Cryptographic Provider v1.0 and generates 32 bytes of random data to use as a seed.

Also, at this stage, the hardcoded ransom note, Restore-My-Files.txt, gets de-obfuscated and the ransomware drops the .txt file in every directory that contains at least one encrypted file.

Victim ID

LockBit creates 2 registry keys with key blobs as values under the following registry hive: HKEY_CURRENT_USERSoftwareLockBit

The two registry keys are:

LockBitfull

LockBitPublic

These registry keys correlate with the Victim ID, file markers, and the unique TOR URL ID that LockBit builds for each system it takes down.

Let’s take the unique TOR URL from the ransom note:

In this example, the 16 byte long unique ID is at the end of the URL, http://lockbitks2tvnmwk[.]onion/?A0C155001DD0CB01AE0692717A2DB14A :

- The first 8 bytes used here (A0C155001DD0CB01)is the first 8 bytes of the file marker that is present in every encrypted file’s end .

- The last 8 bytes (AE0692717A2DB14A) is the first 8 bytes of the Public registry key.

The file marker (0x10 long) is divided into 2 sections:

A0C155001DD0CB01

The first 8 bytes of the file marker and the first 8 bytes of the TOR unique URL ID.

D4EA7A79A0835006

The second 8 bytes are same for all encrypted files in a given run

Also, the value of the full registry key (0x500 long, starting as 1A443C7179498278B40DC082FCF8DE26… in this example) is also present in every encrypted file, just before the file marker.

Share enumeration

For a successful ransomware hit and run, the goal is to encrypt as many files as possible. So naturally, LockBit scans for network shares and other attached drives with the help of the following API calls.

First, the malware enumerates the available drive letters with a call to GetLogicalDrives, then it cycles through the found drives and uses a call to GetDriveTypeW to determine whether the drive letters it finds are network shares by comparing the result with 0x4 (DRIVE_REMOTE).

Once it finds a networked drive, it calls WNetGetConnectionW to get the name of the share, then recursively enumerates all the folders and files on the share using the WNetOpenEnumW, WNetEnumResourceW API calls.

The ransomware can also enter network shares that might require user credentials. LockBit uses the WNetAddConnection2W API call with parameters lpUserName = 0 and lpPassword = 0, which (counterintuitively) transmits the username and password of the current, logged in user to connect to the given share. Then it can enumerate the share using the NetShareEnum API call.

Don’t quit just yet

I an attempt to ensure that LockBit would not be kept from finishing its job by a system shutdown, the developers of this ransomware implemented a small routine that uses a call to ShutdownBlockReasonCreate.

The developers didn’t try to conceal the ransomware as the cause of the shutdown block: the ransomware sets the message for blocking shutdown as LockBit Ransom. Computer users would also see the message LockBit Ransom under the process’ name.

SetProcessShutdownParameters is also called to set the shutdown order level of the ransomware’s process to 0, the lowest level, so that the ransomware’s parent process will be active as long as it can, before a shutdown terminates the process.

If the system is shut down, the malware also has capability to persist after a reboot. LockBit creates a registry key to restart itself under HKCUSOFTWAREMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRun, called XO1XADpO01.

Stop me if you’ve heard this before

LockBit prevents multiple ransomware instances on a single system by way of a hardcoded mutex: Global{BEF590BE-11A6-442A-A85B-656C1081E04C}. Before LockBit starts encrypting, the ransomware checks that the mutex does not already exist by calling OpenMutexA, and calls ExitProcess if it does.

As soon as the ransomware is mapped into memory and the encryption process finishes, the sample will execute the following command to maintain a stealthy operation:

- exe /C ping 1.1.1.1 -n 22 > Nul & ”%s”(earlier version of LockBit)

- exe /C ping 127.0.0.7 -n 3 > Nul & fsutil file setZeroData offset=0 length=524288 “%s” & Del /f /q “%s”(recent version of LockBit)

The ping command at the front is used because the sample can’t delete itself, due to the fact that it is locked. Once ping terminates, the command can delete the executable.

We clearly see an evolution to the applied technique here: in the earlier versions, the sample was missing a Del procedure at the end, so the ransomware would not delete itself.

In the recent version, the crooks had decided to use fsutil to basically zero out the initial binary to perhaps throw off forensic analysis efforts. After the file is zeroed out, the now null-file is deleted also, making double-sure the malware is not forensically recoverable.

Language matters

As we noted earlier, LockBit’s developers wanted to avoid having their ransomware hit victims in Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries. The mechanism used by the ransomware to achieve this calls GetUserDefaultLangID and looks for specific language identifier constants in the region format setting for the current user. If the current user’s language setting matches any of the values below, the ransomware exits and does not start the encryption routine.

Changing the wallpaper

To get the affected user’s attention, the malware (as is typical) creates and displays a ransom note wallpaper. A set of API calls are involved in this process, listed below.

The created wallpaper gets stored under %APPDATA%LocalTempA7D8.tmp.bmp.

In the meantime, the malware also sets a few registry keys so that the wallpaper is not tiled, and the image is stretched out to fill the screen:

HKEY_CURRENT_USERControl PanelDesktop

- TileWallpaper=0 – (No tile)

- WallpaperStyle=2 – (Stretch and fill)

Stack Exchange for crooks

LockBit leverages a very similar service-list to MedusaLocker ransomware. It comes as no surprise that crooks copy these lists, so they don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

The unique Registry run key and ransom note filename that was written by LockBit—XO1XADpO01 and Restore-My-Files.txt — were also seen being used by Phobos, and by a Phobos imposter ransomware. This would suggest that there is a connection between these families, but without further evidence that is hard to justify.

The future for LockBit

A recent Twitter post demonstrates what the future looks like for LockBit. In a recent LockBit attack, the MBR was overwritten with roughly 2000 bytes; The infected machine would not boot up unless a password is supplied. The hash of this sample is currently not known.

The e-mail used for extortion ondrugs@firemail.cc was also seen with STOP ransomware—an uncanny connection. The group behind might be related.

There is also speculation that application Diskcryptor was combined with the ransomware to add this extra lockdown layer. The MAMBA ransomware was also using this technique, leveraging Diskcryptor to lock the victim machine. DiskCryptor is currently being detected as AppC/DCrpt-Gen by Sophos Anti-Virus.

A list of the indicators of compromise (IoCs) for this post have been published to the SophosLabs Github.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the public contributions of @demonslay335 and @hfiref0x.